By Emma Claydon

Have you tried student-made quizzes only to realise that student’s aren’t that great at writing questions? Have they turned out to be more trouble than they are worth? Well, that’s probably because they need some training and the general content needs to be chosen by you.

When learners are trained, student-made quizzes can help to:

- foster a more enjoyable way of learning

- practise all 4 skills

- reduce anxiety towards test taking

- give students more power over their learning

So here’s a lesson idea that I’ve used many times with my IELTS class and has really helped them to get to grips with the reading exam.

Lesson idea:

Helping students prepare for the IELTS reading exam

Procedure:

Max class of 15 with 5 groups of 3 (Min class of 6 with 3 pairs, only 3 articles needed)

Lesson Aims:

- to practise reading strategies (making predictions, skimming and reading for detail)

- to review the features of true, false, not given questions

- to practise rephrasing parts of a text

Authentic Materials

Often when we’ve done tests or reading passages in class, I ask them where they would find articles like these and elicit publications such as The New Scientist, The Ecologist, The Economist and National Geographic or papers such as The Guardian. For lower levels you could also use graded readers.

Preparation

I select 5 different texts between 700 and 950 words each to reflect the length of the exam texts from one of the above publications. Each group will create questions for one article only so I print them a copy. Then for each group I create a pack containing all the articles as they will need this is the second part of the lesson.

Step 1: Review the exam format and question types

I start by eliciting what they know about the reading exam:

- How many questions are there? (40)

- How much time do you have? (60 minutes)

- How many passages are there? (3)

- How long is each passage? (700 – 950 words)

- How many different question types are there? (14)

- Can you name them? (e.g. labeling a diagram, short answer questions, summary completion, sentence completion, true / false, yes / no etc.)

Then I ask which question types they have difficulty with and they usually say true/false and yes/no and summary completion. I then elicit the difference between the two question types (yes / no questions are about the writer’s opinion whereas true/false are about facts in the text). They also find three aspects challenging:

- distinguishing between false and not given,

- understanding the vocabulary in the question or the text

- paraphrasing the question

- employing reading strategies (predicating, skimming, scanning and reading for detail)

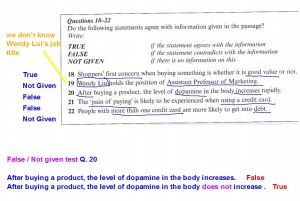

Then I refer back to the reading passage we recently did and elicit the strategy for true, false and not given:

- The questions are in order in the text

- You can make a false question true by making it negative

- Not given means there is not enough information in the text to say with confidence if the answer is true or false.

Step 2: Practise reading strategies: predicting and skimming

Each group then receives their own article. They read the title and make predictions about the content. Then they skim by reading the first paragraph and the first sentence of the subsequent paragraphs. They check their predictions and discuss what they understand about the overall topic of the text. Source: Focus on IELTS

Step 3: Reading for detail and selecting the areas to test

Then they read carefully and choose which areas of the text to test. Once they have gone through the text and identified the areas then they have to write 4 or 5 questions (in text order) and on a separate piece of paper they record their answers with justifications. They must do this together and not divide up the tasks.

Step 4: Writing the questions

During this stage I ask if it’s ok to put some music on low so that they can discuss their questions at a normal level without whispering or getting distracted by others. They all agree and I usually put on something relaxing.

They look back at the questions from the course book to see how they are written (as statements, using modals etc.). They use dictionaries and discuss how to use parallel expressions, this is the most challenging part and I’ll go around monitoring and scaffolding where necessary.

Also I will discuss their questions with them, asking them to justify their answers but I try and not to help them too much. Even if I see that they have created a false question when in fact it’s a not given, I’ll wait to see if the other students will figure this out which will lead to discussions at the feedback stage. I try to focus on clarity and point out if the questions are too easy.

Once they have written their questions, I take pictures to display them on the IWB. For classrooms without IWBs students can take pictures of the questions as they circulate as they will need them in the feedback stage. Alternatively they could be photocopied.

Step 5: Passing the questions round

Students are now ready to answer each other’s questions. They receive a full set of the articles so that they can annotate each one as required. Each group needs a third piece of paper where they will write the title of the article they are working on and their answers with their justification. They need to discuss the questions and try to reach an agreement as a group.

Step 6: Feedback on answers

Once they have passed around all the sets of questions, each group takes it in turn to come to the front and elicit the answers and checking where in the text they found their answers. Students then discuss their answers and it can get quite heated. Sometimes the authors got the answers wrong and their classmates got it right, but this is helpful and usually clarifies the difference between false and not given.

To round off we discuss what was difficult about the task:

- writing good questions

- limited by lack of vocabulary

- ability to paraphrase

- being caught out and really testing the difference between false / not given

Subsequent testing has shown improved results in students reading for detail and not just guessing the answers. The actual score are not important instead the facilitation of student quizzes gets them to practise their skills in L2, develops /and consolidates lessons, encourages learner autonomy and makes lessons less teacher-centred.

Variations:

- Different question types e.g. short answer, sentence completion, multiple-choice

- Here are the answers, what are the questions (looking back over the week to recycle lexical items or grammar points)

- Creating gapped sentences for each other

Recommended Reading

Cambridge Handbooks for Language Teachers

Teaching Large Multilevel Classes by Natalie Hess

Learner Autonomy: A Guide to Developing Learner Responsibility by Agota Scharle and Anita Szabo