By Fiona Deane

Exams make many of us feel stressed. For some students, stress helps them to achieve a higher mark. For others, it turns into “distress” (Stanton, 1983) and this negative stress on their mind (and body) can have an adverse effect on their exam performance, and equally importantly on their day to day life. Unfortunately, some teachers may not be given much training or guidance on how to support students whose stress has got out of control.

Exams make many of us feel stressed. For some students, stress helps them to achieve a higher mark. For others, it turns into “distress” (Stanton, 1983) and this negative stress on their mind (and body) can have an adverse effect on their exam performance, and equally importantly on their day to day life. Unfortunately, some teachers may not be given much training or guidance on how to support students whose stress has got out of control.

This post will:

1) Explain why your students might be experiencing exam stress

3) Discuss academic theory on the relationship between cognition and affect

3) Offer six different activities to help your students get to grips with their nerves

Young people and stress

In 2009, the Guardian released alarming statistics from the Prince´s Trust regarding the wellbeing of young people in the UK. In this report polled by the charity for its Youth Index Study, it reported that “more than a quarter (27%) said they were always or often down or depressed. Almost half of all those surveyed (47%) said they were regularly stressed.” This is clearly not only a British phenomenon. In the context of my sector, teaching English as a foreign language, I have witnessed young people experiencing stress as they grapple with living away from home, with managing their money, with establishing and developing new relationships and, in the context of this post, with preparing for international English exams such as CAE, TOEFL, IELTS or TOIEC.

this report polled by the charity for its Youth Index Study, it reported that “more than a quarter (27%) said they were always or often down or depressed. Almost half of all those surveyed (47%) said they were regularly stressed.” This is clearly not only a British phenomenon. In the context of my sector, teaching English as a foreign language, I have witnessed young people experiencing stress as they grapple with living away from home, with managing their money, with establishing and developing new relationships and, in the context of this post, with preparing for international English exams such as CAE, TOEFL, IELTS or TOIEC.

Why do EFL students suffer from exam stress?

- Economic reality

With the backdrop of the recession looming large and the workplace becoming more and more competitive, young people are bent on acquiring as many qualifications as possible. Having one degree may no longer be enough. This “qualification inflation” or “academic inflation” puts pressure on non-native English speaking students not only to improve their chosen career qualifications but also to gain a high level qualification in English, such as IELTS 6.5 or above or CAE.

With the backdrop of the recession looming large and the workplace becoming more and more competitive, young people are bent on acquiring as many qualifications as possible. Having one degree may no longer be enough. This “qualification inflation” or “academic inflation” puts pressure on non-native English speaking students not only to improve their chosen career qualifications but also to gain a high level qualification in English, such as IELTS 6.5 or above or CAE.

- Expectations

Students may be coming from a family or culture where there are high expectations of young people. I have witnessed this in students coming from Asian cultures. Specifically looking at Korea, Daniel Tudor (2012) says that “Confucianism´s power can be felt in the realm of the national obsession, education. South Korea is famous of its unhealthy preoccupation with exam results and the pursuit of admission to the best universities. This is a legacy of Confucianism´s injunction to self-improvement through education…”. He also adds that “every year there are suicides of third-year high school students at the time of …the university entrance exam”. (For more articles on this, see The Guardian Weekly and BBC articles).

- Lack of life experience

Just this week, I carried out tutorials with my CAE preparation group. A conversation with one of the group, a Swiss 19 year old  young woman, has stayed with me. As we reflected on what she was doing differently that had lead to improved results, she interestingly commented that she felt that she was learning how to deal with stress better. She openly admitted that her high school exams hadn´t been difficult. Now, she was required to pass CAE in a short time frame in order to be accepted onto a Primary Teacher Training programme. This was her first experience of dealing with heightened exam pressure. At the start of the course, she simply had not had the life skills to know how to deal with this.

young woman, has stayed with me. As we reflected on what she was doing differently that had lead to improved results, she interestingly commented that she felt that she was learning how to deal with stress better. She openly admitted that her high school exams hadn´t been difficult. Now, she was required to pass CAE in a short time frame in order to be accepted onto a Primary Teacher Training programme. This was her first experience of dealing with heightened exam pressure. At the start of the course, she simply had not had the life skills to know how to deal with this.

- Unhealthy study-life balance

If they come from highly competitive societies, our students may have developed unbalanced study-life behavior patterns. Returning to the example of Korea, Daniel Tudor (2012) suggests that childhood in Korea is sacrificed in order to gain the necessary marks that they need. “Children enjoy relatively few opportunities to play and socialize with their peers. According to research undertaken by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, Korean children are among the worst in the world at social interaction (thirty-fifth out of thirty-six countries surveyed). In school, children are constantly tested and ranked, rather than taught to work with one another. After the final bell, most are sent to hakwons (private language schools) …When school vacations come, children are not free to relax but instead spend more time in hakwons.”

If they come from highly competitive societies, our students may have developed unbalanced study-life behavior patterns. Returning to the example of Korea, Daniel Tudor (2012) suggests that childhood in Korea is sacrificed in order to gain the necessary marks that they need. “Children enjoy relatively few opportunities to play and socialize with their peers. According to research undertaken by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, Korean children are among the worst in the world at social interaction (thirty-fifth out of thirty-six countries surveyed). In school, children are constantly tested and ranked, rather than taught to work with one another. After the final bell, most are sent to hakwons (private language schools) …When school vacations come, children are not free to relax but instead spend more time in hakwons.”

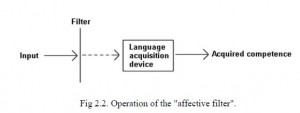

Academic theory and stress: The Affective Filter

Following the ideas of Stephen Krashen (1982), the Affective Filter Hypothesis describes how affective (emotional) factors have an effect on learning a second language (as can be seen in the diagram on the left). Arnold (2009) tells us that “an affectively positive environment puts the brain in the optimal state for learning: minimal stress and maximum engagement with the material to be learned.” Thus, there would seem to be a strong relationship between cognition and “affect”. Neuro-scientist Joseph LeDoux (1996) claims that “minds without emotions are not really minds at all”. Indeed, as NLP guru Anthony Robbins believes “80% of success in life is psychology, 20% is mechanics”.

Following the ideas of Stephen Krashen (1982), the Affective Filter Hypothesis describes how affective (emotional) factors have an effect on learning a second language (as can be seen in the diagram on the left). Arnold (2009) tells us that “an affectively positive environment puts the brain in the optimal state for learning: minimal stress and maximum engagement with the material to be learned.” Thus, there would seem to be a strong relationship between cognition and “affect”. Neuro-scientist Joseph LeDoux (1996) claims that “minds without emotions are not really minds at all”. Indeed, as NLP guru Anthony Robbins believes “80% of success in life is psychology, 20% is mechanics”.

Activities to help students deal better with their stress

So what can we as teachers do to help our students with stress? Here are six activities. They are activities which focus on students developing their own self-reflection and meta-cognition (see my earlier post about this – Empowering your students: what makes me an effective learner?)

- Speaking activity: Are you a good friend?

At the beginning of the course, students are asked to discuss what makes a good friend. In a brainstorm on the board, the teacher elicits “giving good advice” or “being a good listener”. You then tell students that a friend of theirs is excited but worried about moving to another country to go on a language course . The class brainstorms what the student might be worried about and come up with solutions and practical suggestions to ensure the student enjoys their language study programme to the max (inspired from the student book of Ready for CAE (2008, Macmillan Exams) by Roy Norris and Amanda French

At the beginning of the course, students are asked to discuss what makes a good friend. In a brainstorm on the board, the teacher elicits “giving good advice” or “being a good listener”. You then tell students that a friend of theirs is excited but worried about moving to another country to go on a language course . The class brainstorms what the student might be worried about and come up with solutions and practical suggestions to ensure the student enjoys their language study programme to the max (inspired from the student book of Ready for CAE (2008, Macmillan Exams) by Roy Norris and Amanda French

This activity covertly encourages your students to make predictions about a stressful experience and to come up with solutions for an unknown other (which may be more comfortable than finding solutions for themselves). It is a great window for you to see whether they can relate to such stress before and what solutions (or not) they already may have in place for themselves.

- Self-reflection and prediction: How do you predict you will perform in the exam?

This is a more inductive approach carried out just before the mid term mock exam. Students are asked first of all to reflect on their own experience of exam stress in their own countries. Here, pressures of their education culture may rise to the surface. Then they are asked to discuss whether they think their performance in an upcoming mock exam may be affected by nerves (positively or negatively). Students share what possible solutions they know of to reduce stress on their mock exam day. Previous students have come up with ideas such as Steiner exercises, breathing exercises and yoga (I will share more of these ideas in a future post.) Once the students have taken their exam and have their results, I then ask them to recall this discussion and to see if their predictions were right. If they were different, they are asked to say why they are different.

- Understanding the chemistry and biology of stress: “Amy Cuddy´s power poses”

I often use TED Talks with my EFL learners to improve their listening skills, to widen their vocabulary and to develop their summary abilities. So at a significant point in the term, I ask students for homework to watch Amy Cuddy´s talk “Your body language shapes who you are” which explains how stress can manifest itself in the body and how we can reverse the effects of stress. As part of the homework, the students are asked to take notes, be ready to give a summary of the talk (using some of the vocabulary chunks that Amy uses) and be ready to discuss their views. This is an excellent presentation, made powerful by the images, scientific fact and the personalized story telling technique so common to many TED talks. Because the topic is relevant to the speaker herself, it is easy for the students (particularly the girls) to identify with her. So far, all my students have taken an interest in Amy´s ideas. We then tried out Amy´s power poses before the next exams. Each time my students have done this, there have been astoundingly improved results (about 10 – 15% higher marks).

- Deep listening in one to one tutorials

Giving our students the opportunity to voice how they are feeling is crucial when dealing with stress. Tutorials can arise spontaneously, when you recognize that a student would benefit from emergency remedial action, or on a systematic basis throughout the course. Understanding why they may be experiencing stress (which could include some of the reasons given above) is important and this will most probably emerge through “deep listening” (Arnold, 2009); that is, focused listening in a non-judgmental and objective manner. Being sympathetic to their story will validate their emotions (instead of causing them to hide them through shame). It is also worth considering whether you feel the student may benefit from your school´s in-house counseling system, should the stress seem to be out of hand.

- Students share reflections about their stress management to the whole group

In my last round of tutorials, students came up with some really excellent reflections on reasons for their progression, which were related to their own stress management. I took note of the most useful points and then (with their permission) asked some of the students to share their reflections with the whole group. For example, one student reported how they chose to walk into school the day of the exam, revising points quietly in their head as they walked (as opposed to coming in on the bus, surrounded by chatter in rush hour). Another said how they found studying together made them feel less isolated. This discussion involved very fruitful student collaboration benefitting both the “sharer” and the students who took on their ideas.

of the most useful points and then (with their permission) asked some of the students to share their reflections with the whole group. For example, one student reported how they chose to walk into school the day of the exam, revising points quietly in their head as they walked (as opposed to coming in on the bus, surrounded by chatter in rush hour). Another said how they found studying together made them feel less isolated. This discussion involved very fruitful student collaboration benefitting both the “sharer” and the students who took on their ideas.

- The last day before the exam: Student created games

It´s always tricky to know what to do the day before an exam. Exam practice can be inadvisable since low marks can frighten students. On my previous exam course, students requested that we left the classroom space to be in a more relaxed atmosphere. We decided to go to a café. In this group, two Korean students were particularly anxious about the exam the next day. I took coloured paper to the café and asked the Koreans to teach the other (non-Asian) students to make some origami objects. All the students became completely enthralled and lost in this activity. It was a great distraction for both the student “teachers” and for those students learning the art of origami for the first time.

It´s always tricky to know what to do the day before an exam. Exam practice can be inadvisable since low marks can frighten students. On my previous exam course, students requested that we left the classroom space to be in a more relaxed atmosphere. We decided to go to a café. In this group, two Korean students were particularly anxious about the exam the next day. I took coloured paper to the café and asked the Koreans to teach the other (non-Asian) students to make some origami objects. All the students became completely enthralled and lost in this activity. It was a great distraction for both the student “teachers” and for those students learning the art of origami for the first time.

Do write to me and share any experiences and successes you have with stressed students. The life skill of dealing with stress is such an important one in modern life. As one of current exam students said to me recently: “I have learnt so much more than just language on this course”.

Fiona

References & Recommended Reading

Arnold J Affect in L2 Learning and Teaching (2009) Estudios de Linguistica inglesa aplicada

Arnold J Coaching Skills for Leaders in the Workplace (2009) Howtobooks

Brown B The Power of Vulnerability (2010) TED Talks

Gregoire C American Teens are even more stressed than Adults (2014) The Huffington Post

Chakrabarti R South Korea´s schools: long days, high results (2013) BBC News

Cuddy A Your body language shapes who you are (2012) TED Talks

Harmer J The Practice of English Language Teaching (2001) Pearson Education Ltd

Kim K et al Students´stress in China, Japan and Korea: a transcultural study ( 1997) International Journal of Social Psychiatry

Krashen S Principles & Practice in Second Language Aquisition (1982) University of Southern California

LeDoux J The Emotional Brain (1996) Simon & Schuster

Lightbown P. & Spada N How Languages are learned (2006) Oxford

Norris R with French A Ready for CAE (2008) Macmillan Exams

O´Hara M Depression amount the young at alarming level says charity (2009) The Guardian

Oxford R Language Learning Strategies: An Update (1994) http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/oxford01.html

Pert C Molecules of Emotion (1997) Simon & Schuster

Petty G Teaching Today A Practical Guide (1998) Nelson Thornes

Scharle A & Szabó A Learner Autonomy, A guide to developing learner responsibility (2000) Cambridge Handbooks for Language Teachers

Senior R Korean students silenced by exams (2009) The Guardian Weekly

Stanton H E The Stress Factor: A Guide to More Relaxed Living (1983) Optima

Tudor D Korea The Impossible Country (2012) Tuttle Publishing